Shakespeare’s First Folio celebrations

Professor Jonathan Long, Professor in the School of Modern Languages and Cultures and Co-Director, Centre for Visual Arts and Culture shares his experience of the celebrations.

Shakespeare’s First Folio, the first edition of his collected works, was published exactly 400 years ago, in November 1623. There are now only 240 remaining copies of the First Folio in existence. This makes it both very rare and, if not exactly priceless, then extremely valuable. I leapt at the chance to be part of the commemoration events to mark the book’s 400th anniversary.

The Durham-BFI Partnership

A suggestion came forward that we could work with the British Film Institute (BFI), with whom we have had a strategic partnership since 2021. I knew about some of the famous Shakespeare adaptations – Baz Lurmann’s Romeo and Juliet, Gil Junger’s Ten Things I Hate About You, Kenneth Branagh’s ever-growing list of screen versions of the Bard… I’d watched Shakespeare in Love loads of times. But we wanted to do something different. What about older films, like the Laurence Olivier’s wartime Shakespeare films? Or even better, silent Shakespeare? That was a really intriguing question: how do you do Shakespeare without the words?!

The BFI quickly came up with an answer. It turned out that from the very dawn of the cinema as a medium, Shakespeare’s plays had been a source of inspiration for filmmakers. The BFI themselves had recently released Play On!, a curated compilation of clips from early Shakespeare films, some of which date back to 1899. This was just the ticket and the perfect way to celebrate Shakespeare’s First Folio. But we wanted to do more than just show the film – we wanted to offer a multi-media, multi-sensory experience that would appeal to the ear and the taste buds as well as the eye.

Time travelling taste buds

The first thing to think about was the food. Popcorn was the obvious choice for a cinema snack, but this was popcorn with a difference: popcorn with historic flavours developed by Blackfriars restaurant in Newcastle in collaboration with Dr Amanda Herbert from our History Department. There was a lime and chilli flavour to recognise the Central American origins of sweetcorn, and gingerbread popcorn, flavoured (strangely enough) with cinnamon, nutmeg and cloves, which were popular in Shakespeare’s day. It was a kind of time travel for the tastebuds: popcorn, as Amanda explained in her pre-performance talk, was indeed a popular snack among early cinemagoers, while the version we served also evoked the tastes of the Elizabethan age. And did you know that archaeologists have found samples of popcorn that date back to 4000 BCE? No, I didn’t either! But I do now.

Early Shakespeare films

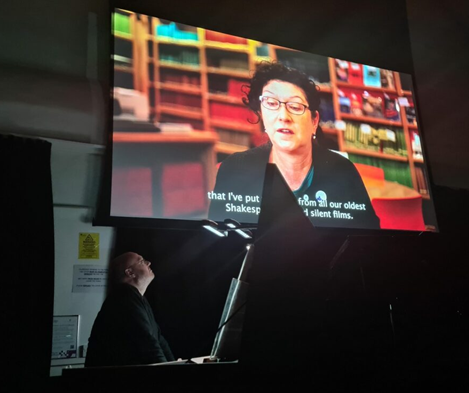

That’s not all I learned. Professor Simon James from English spoke, among other things, about the Victorian performance practices that we can see on some of the very earliest Shakespeare films. Bryony Dixon, a curator at the BFI, had recorded a filmed introduction for the occasion. She spoke about the fragility of early filmstock, the history of Shakespeare on screen, and the technical aspects of early cinema. On the one hand, these were limiting: early films lasted barely a minute, for example. But on the other hand they were liberating, enabling special effects that would have been impossible on the stage.

In true silent film fashion, there was live musical accompaniment by John Snijders and Hector Sequera Mora from the Music Department. They, too, took us on a time-travelling adventure with a fabulous and imaginative programme celebrating Shakespeare’s first folio. It combined seventeenth-century lute and organ music with early twentieth-century arrangements of early lute pieces and music composed, anachronistically, for the harpsichord in the 1920s. The musicians rightly got a spontaneous round of applause as the film came to an end.

Community Event at Blackhall Community Centre

After the successful event in the Music Department Concert Room in Durham, we teamed up with the local arts organisation No More Nowt and took the show on the road, screening the film at the Blackhall Community Centre (what an incredible venue!).

After warming up with medieval games, face-painting, beer or tea or fizzy drinks, and popcorn (again), an audience of almost fifty people, aged from four to ninety, watched the film in proper silent movie style. There was a bit of chatter and conversation (early films might have been silent but audiences definitely weren’t!), coming and going, and plenty of drinks and snacks. It was a brilliant and memorable evening.

A unique experience

So what about the films themselves? Watching silent film seems strange today – they move very slowly, so you have to concentrate on them in a very different way. And the acting styles take a bit of getting used to. But they were full of surprises and delights. Lady Macbeth and her husband were unexpectedly chubby – they really didn’t look like power-crazed murderers. An Italian adaptation of The Merchant of Venice had been hand-coloured, frame by frame, allowing the world of the film to shimmer in rich crimson, emerald, and ochre. Colourisation was an expensive and time-consuming process. Even for international production companies, Shakespeare clearly held prestige.

Best of all, to my mind, were the many clips from a 1909 American version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, in which a mischievous Puck takes enormous and visible glee in the havoc she creates, her main victim being the equally impressive Bottom. His transformation into an ass also showcased early cinema’s capacity for striking special effects.

In his works, Shakespeare returned repeatedly to the idea of the stage as a metaphor for human life. In Macbeth, he writes that ‘Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more.’ Thanks to cinema, though, we can still see these walking shadows from a century ago, strutting and fretting about the screen in ways that remain beguiling. What better way to celebrate Shakespeare’s first folio and while away a cold November night, and mark the anniversary of one of the world’s most important books?

Find out more

- The Durham-BFI partnership was established in 2021.

- If you’d like to share your story or insights into your work, visit our Submit a blog or vlog page to learn more.