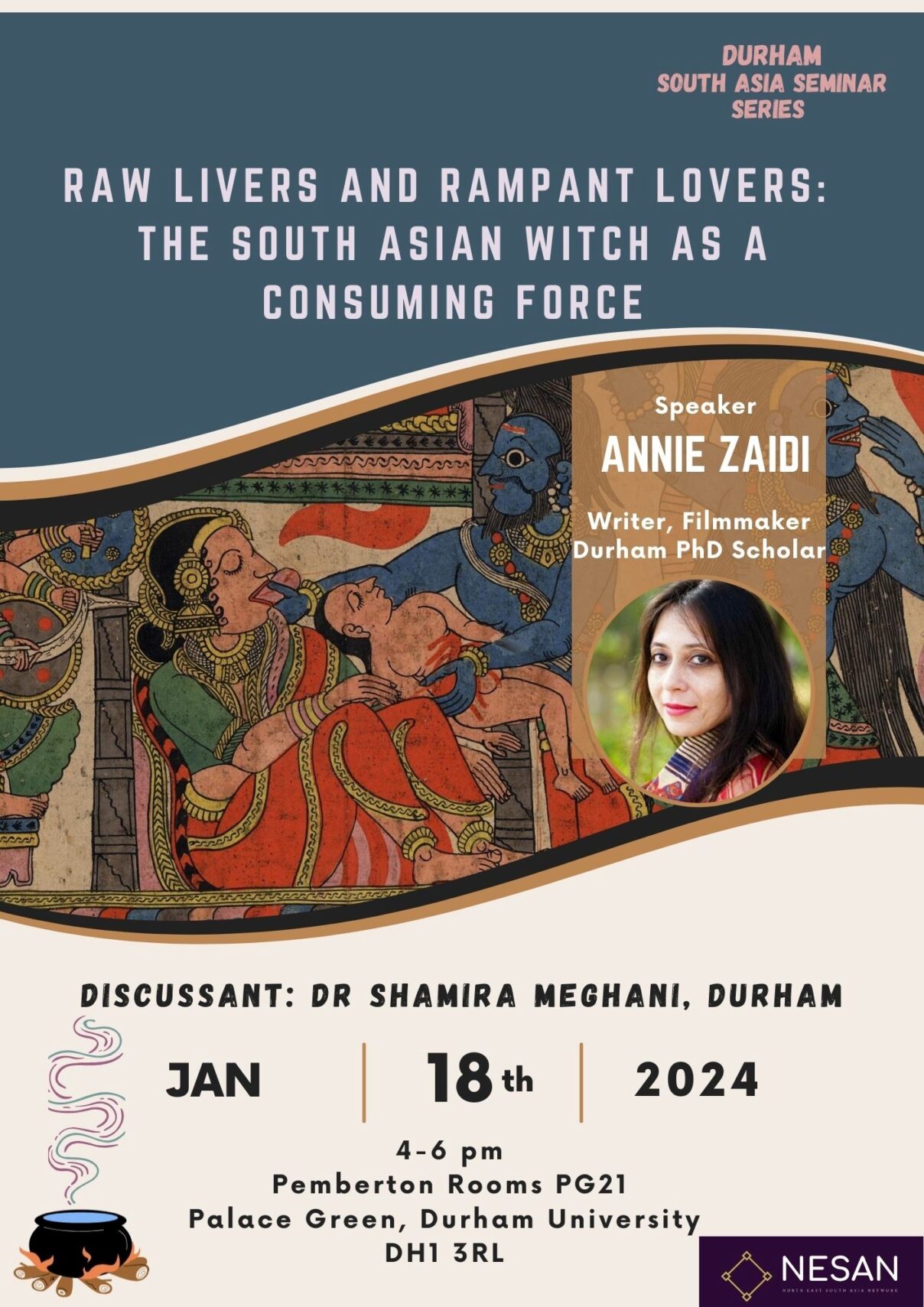

Eaten by a gaze: Witches in South Asian folklore

Annie Zaidi is an award-winning writer and film maker. She is currently studying for a PhD at Durham University. She will be speaking in more depth on the topic of witches at an event, ‘Raw Livers and Rampant Lovers: The South Asian Witch as a Consuming Force’, which will be taking place at the Pemberton Rooms (PG21), Palace Green, on 18 Jan, 4 – 6pm.

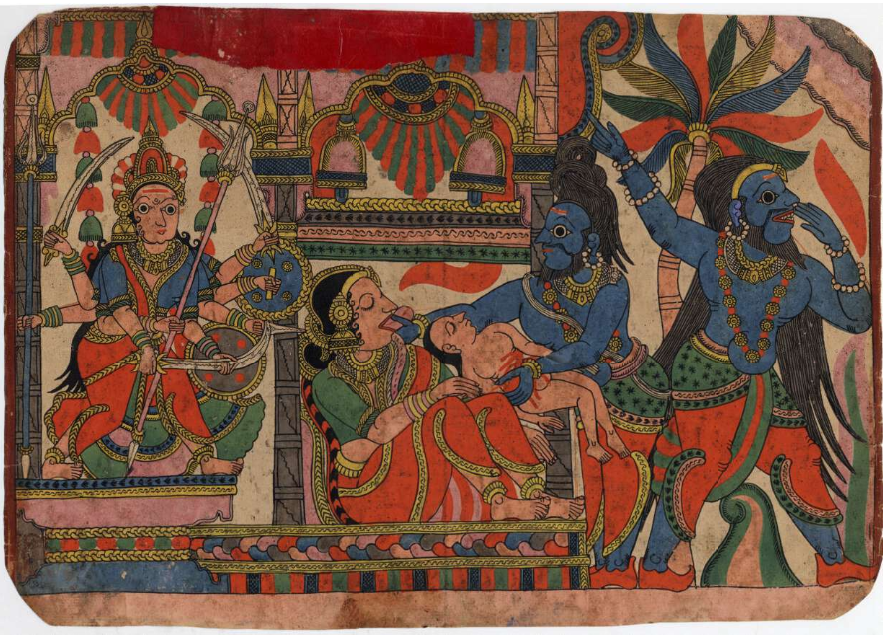

In Western fairy tales, a witch is a scary woman who might ‘eat’ you, cooked or uncooked. In South Asian fairy tales and folklore, she might eat you simply through gazing at you. Worse, she might marry you and then eat you at leisure. In the early twentieth century, Cecil Henry Bompas had documented Santal beliefs that witches eat men.[1] It was said that a girl learning the craft proves herself by ‘taking out a man’s liver and cooking it,’ then feasting on it with the woman who initiates her.[2]

Appetite defines bogeys

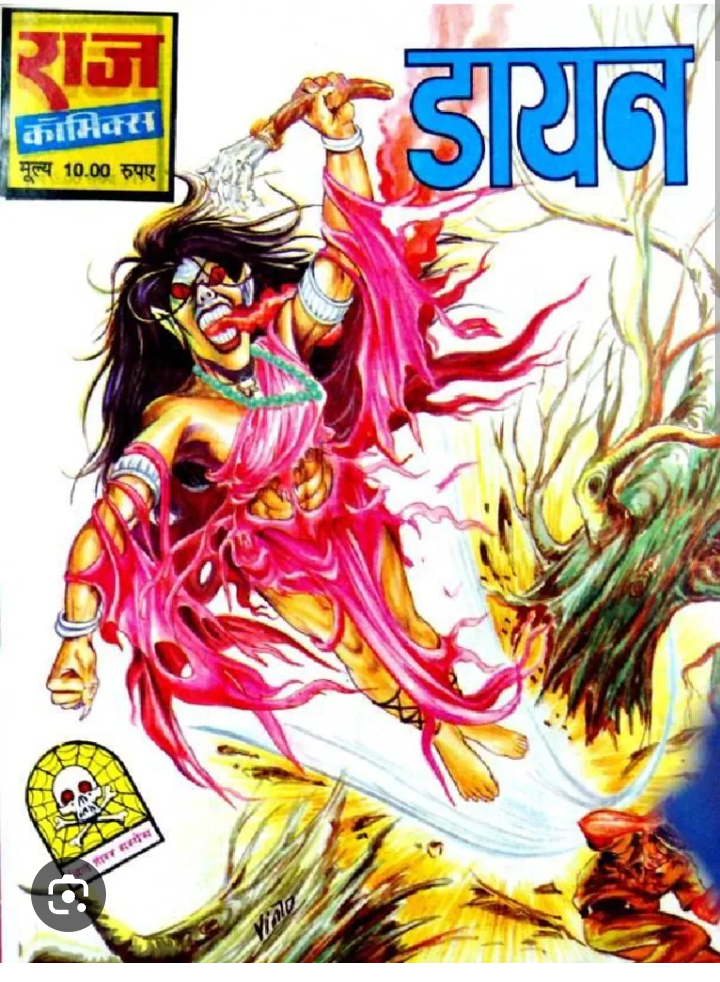

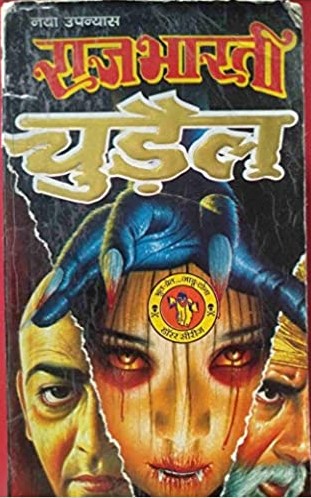

According to writer-mythographer Marina Warner, appetite defines bogeys.[3] If this is so, then the pattern of consumption among witches and witch-like female bogeys from South Asia ought to reveal what kinds of ‘eating’ consign a woman to the category of monster. Apart from Bompas’ collection of folklore from Central India, in western India, R.E. Enthovan found beliefs that witches live on the flesh of corpses. A ‘ghostly dakan’ (known as chudail or ‘churel’ in Hindi) could consume a mortal by living with him as his wife until he ‘becomes emaciated and ultimately dies.’[4] He also mentioned beliefs that spirit-witches ate ‘nothing but flesh’ and if they found no prey, they would even eat ‘the flesh of their own bodies.’[5]

The north-eastern region of India offers more instances of female bogeys that are akin to witches in their eating habits, including the Kaoshe, a vampire-spirit that eats hearts and livers,[6] and the witch-like Skal who eats people’s livers by ‘fixing them with an intense gaze.’[7]

A witch’s gaze

Whether the woman is ‘ghostly’ or a spirit-witch or a mortal witch with supernatural powers, even today, across South Asia, a witch’s gaze or ‘nazar’ is feared as a consuming force and illness or untimely deaths are often blamed upon such a gaze, which occasionally leads to a witch-hunt. Doctor-anthropologist G.M. Carstairs wrote in the 1980s, wrote: “Whenever an adult or a child succumbs to a wasting disease, the onlookers believe that a witch is somehow drinking her victim’s blood and devouring his or her liver.”[8]

These ideas have a long history in the Indian Subcontinent and there are reference to liver and heart-eating witches in medieval texts. Traveling through India in the fourteenth century, Ibn Battuta had mentioned that the witches of Delhi, called Kaftar, could ‘eat’ a person’s heart without touching them.[9] The word ‘kaftar’ is a name derived from the Persian word for hyena, an animal long associated with witchcraft. Nocturnal predators, particularly carrion eaters like jackals or hyenas, are closely associated with witch-lore and in western India, even now, the hyena is known as ‘dakan ra ghoda’ (the witch’s steed).[10] Jackals and hyenas are known as grave-robbers and witches too are believed to ‘eat’ corpses,[11] which makes them kindred creatures. Like humans, hyenas also eat ‘a wide variety of vertebrates, invertebrates, vegetables and fruits and other organic material,’[12] and their association with witches hint at a suspicion of women who are out at night and who do not observe food taboos.

Taboos of meat-eating

For women, meat-eating itself might be held taboo in particular caste contexts. Folklore, however, tends to emphasise their consumption of human flesh or particular kinds of meat that are deemed abject such as raw flesh, carrion, or the flesh of rats and lizards. We find an instance of raw meat signifying monstrous behaviour in a Bengali folktale where a poor and lazy Brahmin moves into a palace occupied by ‘a lady of exquisite beauty’ who marries him. In a ‘state of Elysian pleasure,’ he goes hunting but before an antelope can be cooked, the rakshasi begins devouring it. His Brahmin wife watches her ‘tear off a leg of the antelope’[13] and decides that her co-wife is indeed a demon for eating raw meat. Other stories focus on a broad refusal to rein in their appetites.

In another Bengali tale where a group of rakshasi sisters marries a group of men in order to devour them, one of the rakshasis informs her husband that they ‘eat food a hundred times larger in quantity than men or women.’[14]

Preying on men

Men are at greater risk because, as fairy tales as well as folkloric beliefs suggest, female witches look for men to ‘consume’ and they seek to fulfil their appetites through marriage. This suggests that their hunger for human ‘flesh’ is sexual and their unbridled appetite induces anxiety in patriarchal domains.

It also fuels concerns that, should they fail to be satisfied, women will ‘haunt’ men even after death. Ghosts or spirit-witches are often believed to seek out that which is denied to women in real life.

‘Meat cakes and blood wine’

Writing about the appetites of ghosts in Bengal, Priyadarshini Chatterjee refers to the 16th-century poet Mukundaram Chakravarty’s Chandimangal, which describes a bazaar for ghouls and demons with ‘meat cakes and blood wine, ghee made with human brains and wheel-shaped bread of human paste… juicy paan of human skin, and tubs of bone marrow yoghurt.’[15]

Chatterjee draws particular attention to the Bengali ‘Petni’, the ghost of an unmarried or widowed woman who ‘follows gullible men carrying fresh fish,’ and links her hankering to ‘unfulfilled desire.’ Fish and meat were once forbidden to Bengali widows (as was salt, colourful clothing and long hair).

In the Konkan region too, upper caste widows were intensely monitored and were prescribed fasts like the Chandrayana vrat whereby they fasted incrementally, eating a full meal only on full moon days, then decreasing intake to observe an ‘absolute fast’ on no-moon days.[16] Alongside meat and spices, sex was held taboo for upper caste widows well into the twentieth century, despite legal permit to remarry since 1856.[17] In this context, an unfulfilled ‘ghostly dakan’ or a witch hankering for meat hints at a deregulated femininity.

My research

My ongoing doctoral research on witch bodies and behaviours in contemporary South Asian fiction further suggests that ‘consumption’ by a witch-protagonist is more metaphoric than literal and that the literary witch serves as a vehicle for the expression of popular ideas about the ways in which women’s bodies and appetites are contained.

Find out more

- Hear Annie talk in more depth on this topic at Raw Livers and Rampant Lovers

- Find out more about the fascinating research in food studies at Durham

- Learn more about opportunities for postgraduate opportunities in the Department of English Studies

- Find out about studying a PhD in Creative Writing at Durham

- Read more of our staff blogs.

[1] Cecil Henry Bompas Tr., Folklore of the Santal Paraganas, London, David Nutt, 1909; pp 426

[2] Bompas, 1909; pp 424

[3] Marina Warner, No Go The Bogeyman: Scaring, Lulling, and Making Mock, Chatto & Windus London 1998, pp 10

[4] R.E. Enthovan Ed., Folklore Notes Vol 1 – Gujarat; British India Press, Mazgaon, Bombay, 1914; pp 152

[5] R.E. Enthovan, The Folklore of Bombay (first published: 1924, Oxford); Asian Educational Services, New Delhi-Madras, 1990; pp 194

[6] Bhairav and Rakesh Khanna, Ghosts, Monsters and Demons of India, Blaft 2020, pp 182

[7] Bhairav and Rakesh Khanna, 2020, pp 368

[8] G. M Carstairs, Death of a Witch: A village in North India (1950-1981) [Hutchinson & Co 1983] pp 56

[9] Bhairav and Rakesh Khanna, 2020, pp 105-106

[10] Manan Dhuldhoya, ‘Not the Witch’s Steed: Why the Hyena is India’s Most Misunderstood Predator’ in roundglasssustain.com; Aug 18, 2022; https://sustain.round.glass/species/striped-hyena/ [accessed 14 December 2022]

[11] Enthovan, 1914; pp 152

[12] Jürgen W. Frembgen, The Magicality of the Hyena: Beliefs and Practices in West and South Asia; Asian Folklore Studies, 1998, Vol. 57, No. 2, pp. 331-344

[13] Rev. Lal Behari Day (Ed.), ‘The Story of the Rakshasis’ in Folk Tales of Bengal, Macmillan and Co, 1889; pp 64-92

[14] Rev. Lal Behari Day (Ed.), ‘The Story of the Rakshasis’ in Folk Tales of Bengal, Macmillan and Co, 1889; pp 270

[15] Priyadarshini Chatterjee, What do ghosts in Bengal eat?; Scroll.in Oct 29, 2022; link: https://scroll.in/magazine/1036017/what-do-ghosts-in-bengal-eat [Accessed Oct 30, 2022]

[16] R.E. Enthovan, Folklore Notes Vol II Konkan, British India Press, Mazgaon, Bombay, 1915; pp 8

[17] S.N. Agarwala, Widow remarriages in some rural areas of Northern India; Demography 1967; 4(1):126-34; doi: 10.2307/2060356